Curatorial Statement

By Curator Chia-Lin LEE

Videogames ate our quarters, won our hearts, and rewired our minds.

—— J.C. Herz

Let’s go back to the 1950s – 1960s. At that time, computers were huge in shape and expensive in price, equipment only accessible to universities or research institutes. In 1952, Sandy Douglas who was then a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cambridge developed one of the first games in electronic game history – the tic-tac-toe game “OXO” – with an EDSAC computer. After that, different tabletop chess games were developed into computer versions, allowing modern military wargaming to enter into computing. In 1962, in order to let various users use the computing resources of the massive computer at the same time, the so-called “time-sharing system” was developed; also, another game “Spacewar!” was able to be operated on MIT’s PDP-1 (Programmed Data Processor-1). The time-sharing technology has permitted two players to be connected and fight against each other. This led to the concept of the “personal user”, allowing people to seemingly own a computer of their own.

Games are often used as a display method of computer technology development, helping people to better comprehend some new technologies or functions. In terms of human-machine interface development and computer hardware popularization, games have played an important role. Not only did they rewire our brains but also reshape our outer forms by growing calluses on them. The very famous examples would be Microsoft’s Mines, Solitaire, and Hearts. In the 1990s, these games were built in the Windows systems by Microsoft, allowing users to be more familiarized with the mouse operation. Afterward, the concept of “gamification” together with the digital interface has been vastly applied in different fields, including education, marketing, business management, crowd outsourcing, health management, and other blockchain games featuring the play-to-earn mechanism.

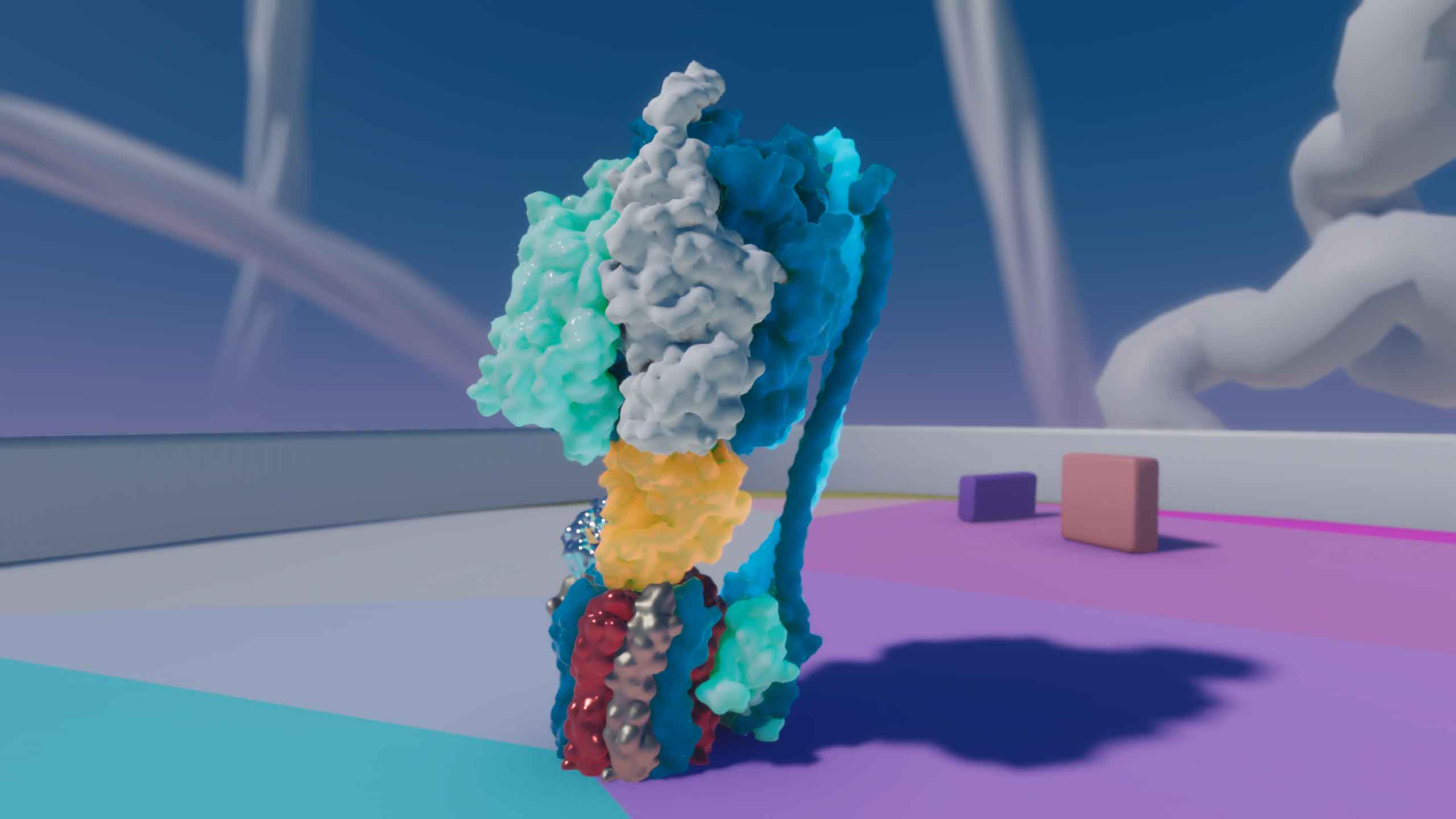

Media theorist Claus Pias mentioned that “the world of the (digital) computer world is itself already a game world” in the book “Computer Game Worlds”. Computers’ operations are based on a set of symbols and clear starting points, just like games. The artistic works created based on computer games have also inherited this essence. The works are sets of procedures, rules, and coding. People can only see its appearance once it is played or executed, or else, it remains in a non-materiality state for most of the time.

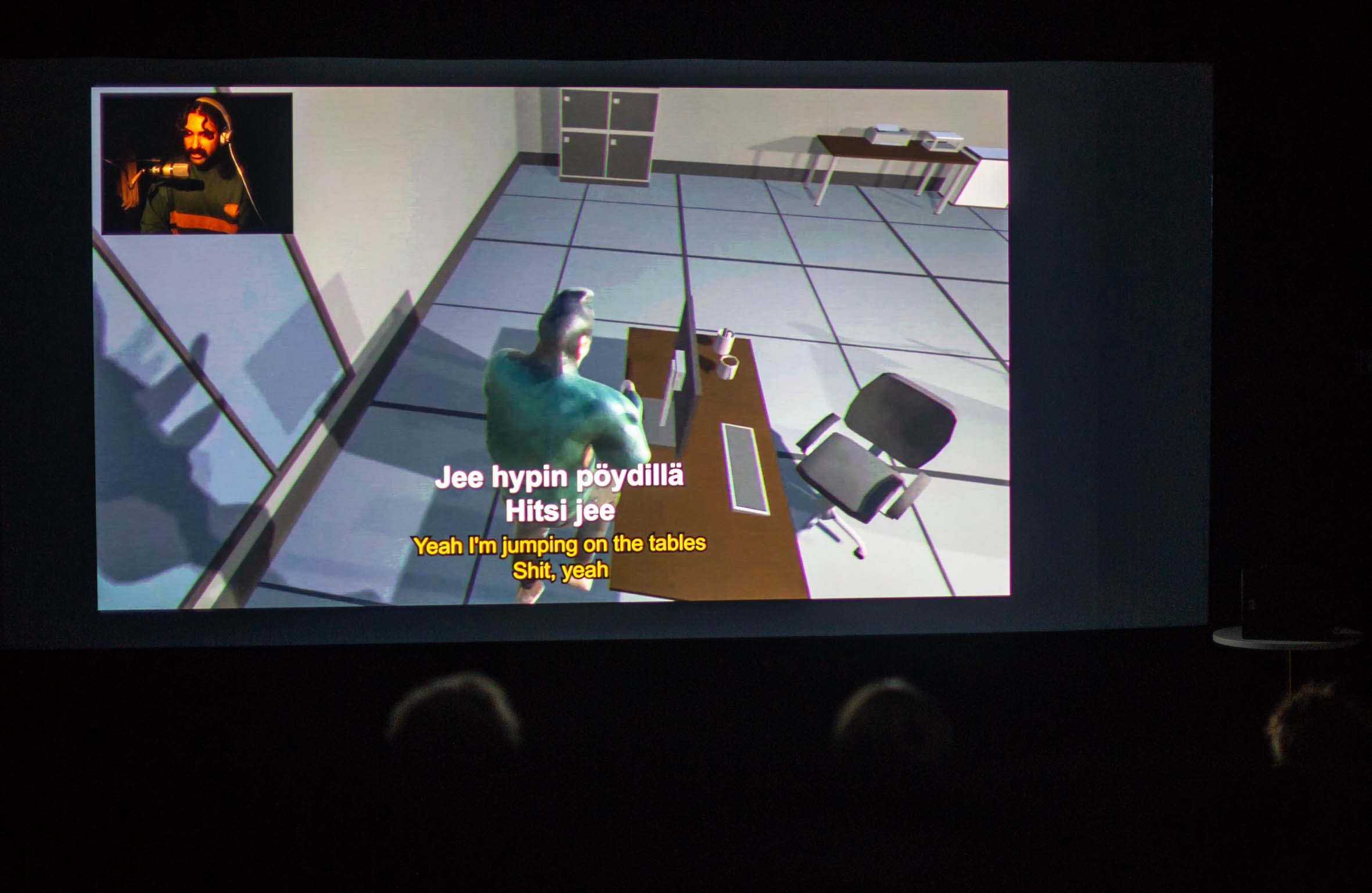

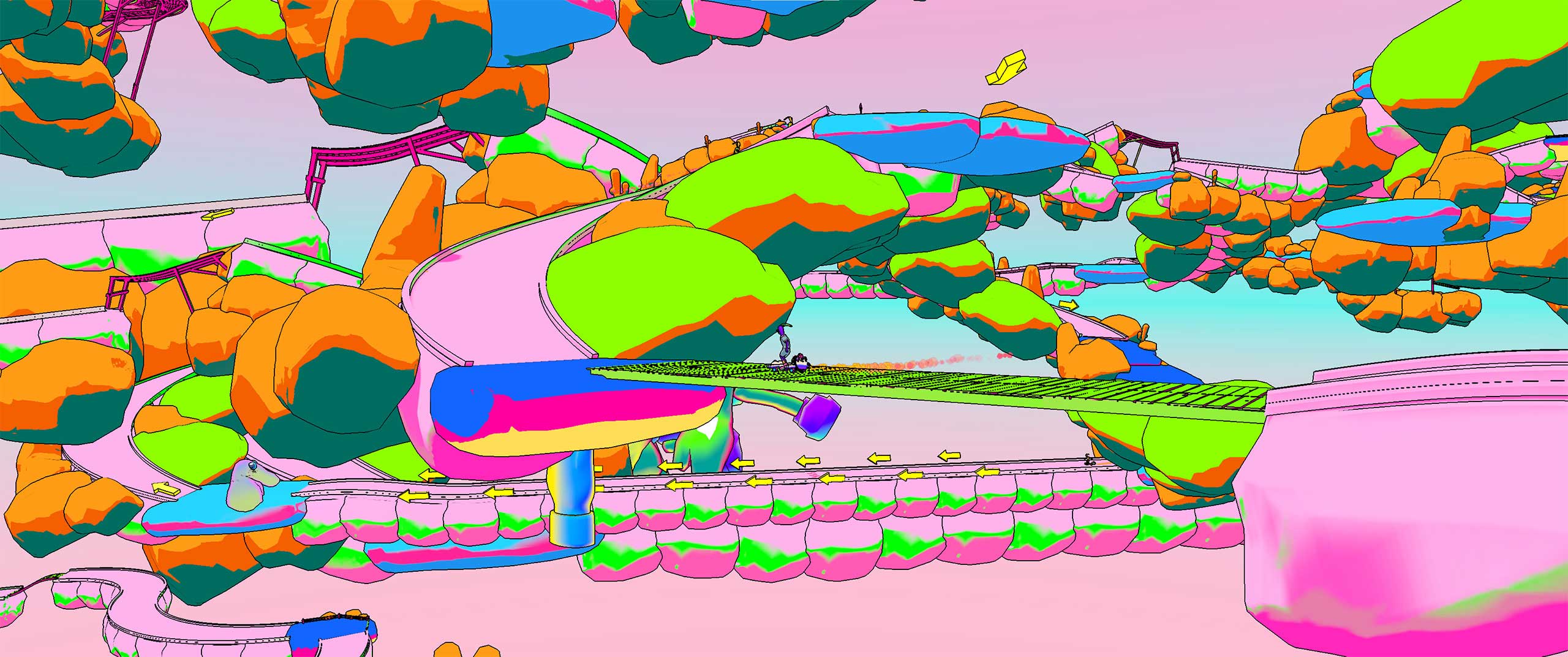

To have an acumen over the intersection of video games and contemporary art from the overview of technological development, we would turn to game engines as integrated development environment that appeared in the 1980s. Game designers were able to get rid of the design development with pen and paper. Then, in the 1990s, when game engines had become the development mainstream, works using engines gradually appeared in the creations of contemporary art. Some of these pieces inherited the DIY culture, hacker culture, and free/open-source software movements of the last two decades, somewhere between 1980 – 1990, as their nutrients. Certain paradigms could be outlined among these creations – the glitch as the aesthetic setting, hacking into the game system, modding, or using games as the narrative method.

Thus, nowadays when more creators are using the game engines, what else may emerge? In “Game Works: On the Aesthetics of Games and Arts”, the designer/curator John Sharp has divided the relationship between games and arts from a massive amount of examples into four categories: Game Art, Artgames, Artist’s Games, and Games as a Medium. Could the framework still be used in the comprehension of current creations? Or else, have the boundaries become more blurry?

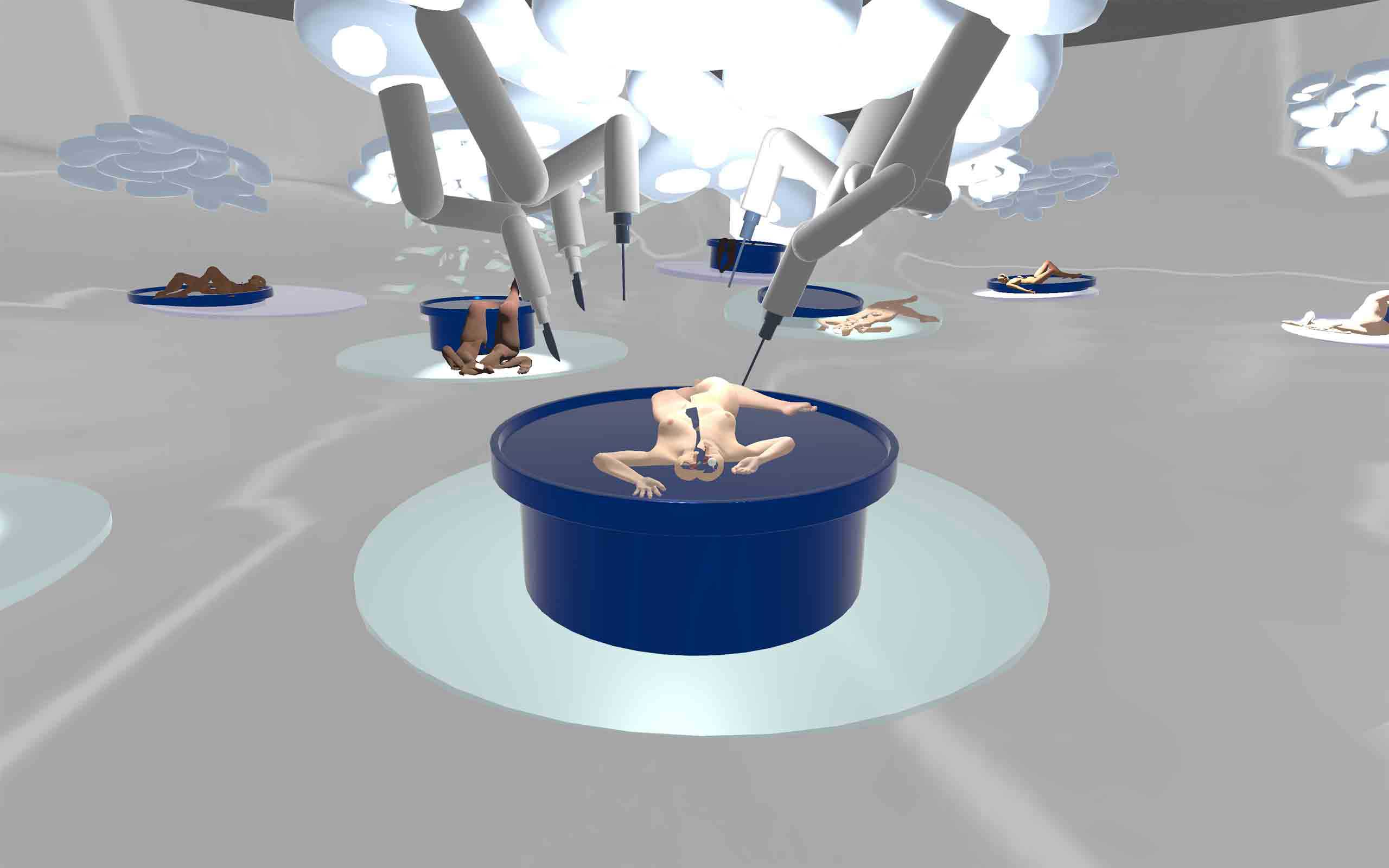

On one hand, the exhibition theme “A-Real Engine” alludes to video games as an engine full of energy that keeps driving the development of digital culture. In the common formats of contemporary arts, such as kinetic installations, network art, technology art, encrypted art, and other creations in different aspects, such corresponding technological driving force can always be identified. Certainly, computer games are also included; they can even be evolved into creations like machinima. Computer-game-related software and hardware technologies, design mindset, and contents generated by users have all injected a stream of freshwater into artistic creations. On the other hand, the privative prefix, “A-” of “A-Real” refers to an explicit rejection of the distinctions between real/unreal, online/offline, and virtual/real. It is most probable that such a distinction may be invalid and has never been applied. In fact, games are a kind of reality.

Game engines are the environments and rulesets of game development and operations, whereas exhibitions are the environments in which artworks are being experienced or even completed. Artists build a brand-new narrative through computer game concepts and elements or deconstruct the game mechanism by disassembling the engine. Under guidance, the audience can further understand their own standpoints, or even find a path to escape from the system’s control, becoming a potential rule breaker. Additionally, repairing game consoles that preserve and recreate games that once brought pure joy to people is also an approach, and is one that makes people willing to spend all the coins in their pockets — all of these aspects are presented in the exhibition.

Venue

National Taiwan Science Education Center